How can we help teenagers to be more active?

In almost every region of the world, overweight and obesity among children and adolescents is a public health problem. There has been no progress in stemming the rate of overweight and obesity in children under 5 years in nearly 20 years, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

This is a problem, because we know that when people live with overweight or obesity near the start of their lives, it often becomes a challenge throughout their adult lives.

What’s the problem with being inactive?

Young people may not be thinking very much about their risk of developing cancer. But the habits laid down in youth can last a lifetime. Our evidence shows that being active reduces the risk of colon (part of the bowel), post-menopausal breast and womb cancers.

Perhaps more importantly, being physically active also helps reduce our risk of living with overweight and obesity – a cause of at least 13 different types of cancer. Put simply, excess weight results from an imbalance between the energy we take in through our diet, and the energy we expend through being active (and other bodily functions). While we need to consider wider issues related to our ability to access a healthy diet, and managing stress and sleep levels, part of the solution involves being more active.

Are screens a particular problem?

Screens, and particularly mobile phones, have been blamed for a range of social and health problems among young people, including:

Evidence from our 2018 Diet and Cancer Report revealed convincing evidence that more screen time for children (from mobile phones but also using computers at school and watching devices during leisure time) makes weight gain more likely, as well as overweight and obesity.

The reasons for this are mixed. We tend to watch screens while sitting down, which uses less energy. Watching screens can also encourage us to eat more than is needed, not least because of exposure to adverts for unhealthy food and drinks, which young people may be particularly susceptible to.

The WHO lists limiting screen time as one of the ways to prevent and manage overweight and obesity in young people – but it’s only one.

What are the barriers to getting more active?

Young people’s experiences differ but, looking at the evidence and talking to parents and teenagers in the UK, a few common problems are highlighted:

- Underfunded / poor-quality equipment in public spaces (that may also feel unsafe to use).

- Cost – young people often don’t have a steady income, and gyms/clubs/sports can be expensive. Young people need access to parks and sports fields in their neighbourhoods.

- Travel – young people are often dependent on others for travel, which makes active travel – including safe routes to walk or cycle to school – and good public transport infrastructure so important (see below).

- Lack of options – children and young people in the UK are often offered activities such as football, netball and cross-country, but many want to try out less conventional sports such as yoga, dodgeball or trampolining.

- Gender – there is a significant decline in young girls taking part in sport, and parents of girls highlighted particular barriers to participation around body image, concerns about sweating and clothing, and lack of private changing spaces.

Elsewhere, a 2022 study looking at Botswana, Ethiopia, South Africa and Zimbabwe identified barriers around funding, but also highlighted community safety and a general lack of infrastructure as challenges.

What solutions are working around the world?

When developing ideas and designing policies to tackle overweight and obesity among children and young people, one voice is often unheard – that of young people themselves. From 2018–23, World Cancer Research Fund was involved in an innovative EU-funded project called CO-CREATE, which aimed to change that by putting young people at the forefront of tackling the obesity epidemic in Europe. The youth representatives on the project came up with 4 demands to policymakers, including “Offer all children and adolescents free, organized physical activities at least once every week.”

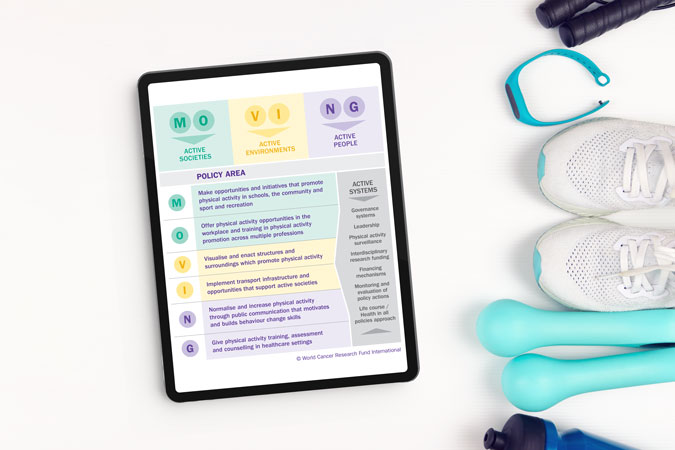

Using what they learned as part of the CO-CREATE project, our Policy team have devised a policy factsheet on physical activity, outlining the best ways to meet our Cancer Prevention Recommendation to be physically active.

Of all the information in the factsheet, some policy recommendations would specifically benefit children and young people, if acted on by governments around the world. These include:

- Initiatives that optimise opportunities for physical activity (including walking and cycling to and from school).

- Active play before and after school, as well as during recess and lunch breaks.

- Reduce sitting during classes.

- Policies to priorities active urban design, like ensuring access to open/green space or walking and cycling infrastructure where people live.

To keep people informed about both the need to be active, and the opportunities available to them, we also recommend:

- High quality physical education in school curricula.

- Enhanced physical activity training for all teachers.

And some of these innovative policies are already being undertaken in parts of the world. There are many policies recorded in our MOVING database mandating physical activity in schools, broadly ranging from 2–4 hours per week, depending on age and country.

And it’s not just dedicated PE sessions. Italy’s Scuola attiva kids aims to promote a culture of wellbeing and movement among not only students but teachers and families as well. In Finland, the Students on the Move programme encourages young people to sit less and move between breaks. Belgium’s Adventurous Activity initiative offers young people the chance to try out high and low ropes, tree climbing, rowing, BMX, skiing and orienteering.

Yet parents we spoke to suggested that there also needs to be a reframing of how PE is seen in school. One parent in Surrey, UK, said: “If you’re really good, you tend to do loads as part of a club, but there seems to be very little for those who aren’t any good.”

“There’s different aspects of sports. There’s one where you’re trying to create lifelong fitness for young people to engage in sport as part of a healthy lifestyle. And there’s another part where you need competitive sport to provide appropriate challenge” – Jennifer Cole, teacher and parent of 3, Brunei

“Emphasise fun so everyone can join in. Let people compete and win something but focus on beating personal bests rather than being top of the class so it’s not exclusive. Why not offer points or vouchers for those who increase their steps the most, not the ones with the overall highest numbers, so you’re encouraging people who don’t do anything?” – Mike, parent of 3 including 2 teenage girls, UK

Active travel was another key concern for parents – and is also one of our policy recommendations, including:

- Transport policies, systems and infrastructure that prioritise walking, cycling and use of public transport.

- Road safety actions for pedestrians and cyclists.

Active travel, which has the additional benefit of helping countries meet climate commitments, is already being promoted in many European countries. Austria’s Kindergarten Mobility Box aims to make walking and cycling the norm from a young age, and Belgium has similar scheme.

Perhaps, rather than just focusing on crisis-driven solutions to an increasingly inactive world, we need to listen more to young people about the changes they want to see in their world, alongside implementing policies that make it easier for everyone – especially young people – to move more and sit less as part of their everyday lives.

Want to get more active?

Check out our resources to help you get moving – written by experts